My English teacher for junior & senior year of high school ( Donald X Nekrosius) is to blame for this story.

He had positive impact on my self-image simply because he told me I was a good writer. And I’ve come to believe that I am…now. But then? I saved my papers from his classes for years because he made me feel so good about them. I went back and read them and realized something — they’re not that great. There’s sound ideas but also typos and unnecessary repetition — things that were remarked upon along with his lengthy comments and genuine engagement with the ideas and how they were expressed.

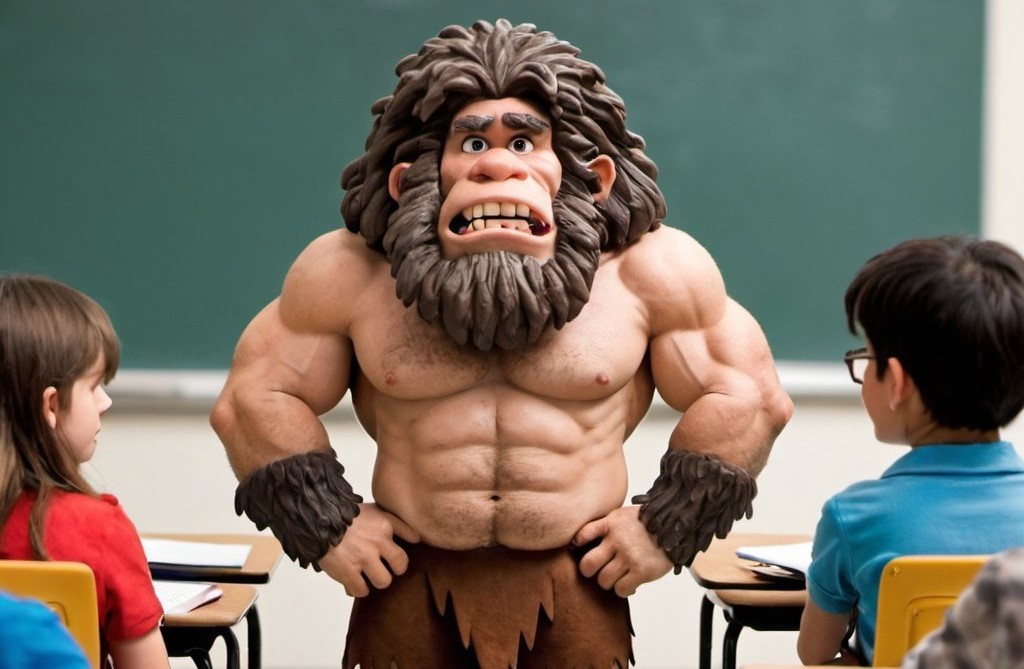

He also provides me with a strong point of comparison to my oldest child’s teacher for grade 11 English. We’ve spent a lot of time in our house talking about things that can be done, tweaks that can be made to meet this teacher’s expectations. But the year has revealed that this educator is holding onto some mental models that, while not uncommon, set up an environment where learning and success in the class don’t go hand in hand. This is a summary of the beliefs at the heart of some truly disheartening practices.

1. The classroom is a zero-sum environment where opportunity and education are finite resources that, if extended to one, have to be wrenched away from others.

The English teacher in question expressed a sentiment that is not uncommon. She stated that one student getting additional time or make up opportunities is unfair to the rest (who I guess don’t though there’s no real reason they couldn’t). We get so used to hearing opinions like this, we assume there is unassailable logic here, when in fact it’s comically absurd.

If a student commits themself to continue rewriting the same paper or retaking the same test time after time till they reach some goal (an effort, by the way, no student ever makes), what is taken from other students?

The example is merely a symptom of the disease at the heart of this. Some teachers, administrators, and parents decide that students are in competition with each other. The school of thought goes: The job market is competitive. Competitive jobs go to those who’ve been to the best colleges. The best colleges are competitive in selecting students. Thus, students are always competing with one another. And they are the fair, unbiased referees (more on this in number 5).

Seems reasonable but the assumptions made getting there are just…incredibly old. The job market has never been more unpredictable — some jobs and employers and fighting for mediocre talent while others can have their pick of the best. Yes, the best management consultant jobs go to graduates of the best colleges (real quick — name a K-12 student who wants to be a management consultant). I will concede that graduates of the “top” colleges earn more and thus are highly competitive but that represents a sliver of the population and the “best jobs” is very much an eye of the beholder thing.

Furthermore, being competitive doesn’t prepare someone for the workplace (other than being the office bully or the person that presents others ideas as their own). At work, they will be expected to cooperate.

In a cooperative educational environment, incentives can be placed on collective success in learning. The top students will help others reach an agreed upon standard. These students will still gain an advantage because they will get early experience with coaching and organizing and thus develop higher earning job skills.

2. Students are lazy, conniving, and have a total disrespect for their teacher’s time.

If you assume students are always trying to get away with something and proceed to treat them as such, you will find it to be true. My child’s English teacher begins the first class with slides and a syllabus that aggressively establish a number of rules regarding the acceptance of student assignments. I could probably explain the laws of thermodynamics more concisely than I could go through her criteria for accepting work. My question is Why?

Because she assumes bad faith on the part of students and treat them this way, they will inevitably put more energy into classes where the teacher treats them like a human being. That may mean being lax with assignments for this teacher’s class. And then she will think she was right to expect the worse.

Turns out, expecting the worse of people, and showing it by ranting ad nauseum about all the rules in place to avoid their inherent terribleness, is a self-defeating tactic. Children and teens have great intuition. If they sense that the teacher cares more about their time than any other factor, they will have little respect for the teacher’s time. And because the environment is likely competitive, they will see any convenience or contentment for that teacher as an unpleasant experience for them.

3. Exceptions are “slippery slopes” to anarchy.

“We aren’t equipped to handle tons of requests like that.” “It is our policy.” “If we do it for you, then you have to do it for everyone.” These are the clarion calls of the slippery slope argument — one of the most pernicious logical fallacies out there. It’s also something that lies at the heart of most bigotry. When marriage equality was debated, I honestly once heard “If we allow two men to marry, soon we’ll be marrying people to box turtles.” I’m sure there’s more than one golf club that has argued If we let in the Jews, soon we’ll have Asians and blacks?!

At the heart of the slippery slope argument is a very real dilemma for the human animal. We have an inherent understanding that life is chaotic and arbitrary and try to shield ourselves from that with rules and policies. And a good rule or policy is one that is staves off the gaping chasm of uncertainty, thus has to always befollowed. If is not followed once, then it never has to be.

The problem with this is that the bulk of people are happy to conform and will despite any outliers. A good rule is not one that is always followed. A good rule is one where most are inclined to follow it because it has inherent value. And that’s what terrifies a bad teacher.

In their hearts they are insecure about the overall value that they are offering. This probably developed because the individual was already poor at other elements of teaching, like creating engaging lesson plans or having empathy for children.

If you believe there is inherent value to your way of doing things, you don’t worry that the exceptions will soon lead to anarchy. You think of them as what they are — exceptions. And, what if it does turn out that most people desire the exception? Well, then you just learned something didn’t you.

4. Allowing a student to fail can be a valuable “life lesson.”

Consider this — you’re giving a test and a student who’s having a bad day (or even just being a jerk) refuses to take the test and puts their head down when everyone else completes it. Doesn’t it make sense for them to face the consequence of not having another opportunity at the test and receive a zero?

Well, it depends on what your purpose is. If it’s to make sure they obey authority because this is a key lesson to learn in life, I disagree but, sure — that is a valid approach for this strange goal.

But if your goal is for them to reinforce the learning of content you feel has value, flexibility may be necessary. That flexibility may also prove that you are an authority worthy of some obedience.

If you have real learning objectives that are enriching to students lives, failure is never a positive. Preventing a student from practicing or demonstrating learning should be an extreme saved for unique circumstances I won’t waste time trying to think of. The only lesson students get out of failure is that they are a failure. Why would you want to provide them with that?

5. Educators can be fair and unbiased

I remembered something else when I looked at my old high school essays. Mr. Nekrosius had us put names on the back of papers, so that the name doesn’t influence his judgement. I’d argue it’s because he understood that bias exists. More importantly, he understood that he was not free from it. Why on earth would he be? It would be unnatural to the point of psychopathy for a person who meets dozens of students at a time, year after year, to not form patterned impressions of those students based on their experience and observations.

When people believe that they are fair and free from biases, they simply harden those rapid impressions into iron-clad truths in their minds. This means they become more biased and more of a slave to their impressions. By knowing that you are biased and learning what those biases are, you can adapt accordingly, question yourself, and draw better conclusions.

In conclusion…

Reading this, you may decry my assessment because “this is the way I was educated and I turned out fine.”

My response: Did you?